One of the first issues I became passionate about was keeping kids safe from guns. Why? While I was a pediatric resident in San Diego, the school shootings at Santee, California occurred. This was just two years after the horrific events at Columbine. I saw kids coming to clinic, with non-specific complaints and in the end, not wanting to go to school. Parents had questions about how to best handle their kids’ (and their own) fears.

Why did this happen? How could it happen here? Should kids be allowed to stay home from school? What can we do from preventing this horrible thing from happening again?

This experience set me on the path towards advocating for children’s health within the context of public health. I saw just how this type of violence affects individual families but also its effects on the larger community. I started a project to simplify the screening for the presence of guns and other risks for childhood injury during clinic visits; passed out free gun locks to families who told me there were guns in the home; and distributed play date safety cards to families.

Over 75% of gun injuries and death are the result of children with easy access to guns that are improperly stored. When these types of events happen, it is usually at a friend’s house or their own. Now we see these headlines daily: a toddler who finds his mother’s handgun in her purse and accidentally shoots himself; school aged boys who come across a loaded gun during play and it accidentally discharges; a teenager with depression or is bullied who has easy access to a gun and commits suicide or decides to bring it to school as an act of revenge for perceived wrongdoings. The one thing that comes out of these events is that they are brought to our attention. The endless stories can cast no doubt that guns and kids are a public health epidemic. On the other hand, hearing these headlines daily can leave us feeling no longer shocked that these events happen. That somehow it is part of our daily fabric living in this country. Too many children’s lives lost, too many senseless events that could have been prevented. Too many families torn apart and affected by guns.

BUT DO NOT GET NUMB. Sometimes it can feel like there is nothing we can do as a society to change things because too many of these events happen EVERY DAY. However, we have a responsibility to do what we can for our own children, for those in our care, for those in our global community. No one is immune to these events.

We must remain vigilant and continue to do what we can as responsible adults, providers, parents, and community members. We can join organized groups that advocate for action at the federal level to pass sensible gun safety laws and ensuring access to comprehensive mental health services. There are things we can do each day by knowing what safety risks might be present in the places our children are allowed to play. We cannot assume that children will know the right thing to do when they stumble upon a gun.

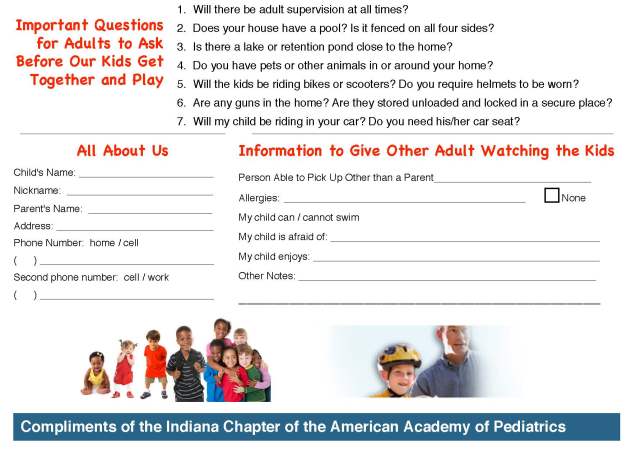

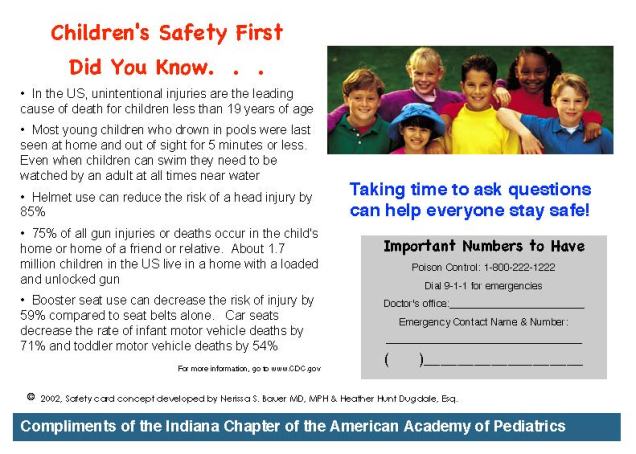

Playdate safety cards are meant to help parents ask each other about potential safety hazards in the environment in which children play. It is hard to ask someone if they have guns in the home, and even more so of friends or acquaintances you have known for a while but may have never thought to ask. These playdates cards can help start the conversation.

While this is a small measure and will not “cure” this epidemic, it can be a step towards prevention of another event.

When parents arrange a playdate for their children, they usually share information about their children including any food allergies and any fears of pets. Parents exchange phone numbers or emails in the process. This is the ideal time to ask whether there are guns in the home. It is up to the individual parent what to do with that information if the answer is yes. However, if you don’t ask, you won’t know–and I would argue it is always better to know.

The cards can be printed on cardstock. You can stick it on the refrigerator with a magnet or in an address book once completed. You can trade them when you meet another parent. The crucial part is that it has statistics and a section with questions to ask the other parent. If you cannot bring yourself to ask spontaneously, having these cards can give you ideas for how to start the conversation. The first few times may feel awkward, but after that it becomes easier.

Download the playdate card file here.*

*A special thanks to Heather Hunt Dugdale, Esq. for working with me in those early days in San Diego on this tool. Another heartfelt thanks to one of my first mentors, Dr. Bronwen Anders, whose clinic I worked at during residency, who supported and helped me gain the confidence to move this cause forward.

Educate yourself about this issue & what you can do to help this cause.

More more information:

- American Academy of Pediatrics, HealthyChildren.org website has great parent friendly resources including: Gun Safety: Keeping Children Safe

- http://momsdemandaction.org

- http://everytown.org

When families face chronic diseases, it is especially important to encourage their active participation with the medical team. This is the hallmark of the “chronic care model,” which encourages medical providers and the patient/family to work together. Chronic diseases often require lifestyle and behavior change to maximize outcomes. This is especially true in pediatrics and behavioral conditions. Published clinical care guidelines for all pediatric behavioral/mental health conditions (such as ADHD) highlight parent training and behavioral interventions as “first line” treatments.

When families face chronic diseases, it is especially important to encourage their active participation with the medical team. This is the hallmark of the “chronic care model,” which encourages medical providers and the patient/family to work together. Chronic diseases often require lifestyle and behavior change to maximize outcomes. This is especially true in pediatrics and behavioral conditions. Published clinical care guidelines for all pediatric behavioral/mental health conditions (such as ADHD) highlight parent training and behavioral interventions as “first line” treatments. It is important to help families become advocates for their children. For children with behavioral conditions, this is even more important because children’s behaviors often can lead to stress and strain on peer relationships and functioning in school. However, there are terms or abbreviations that need to be explained in clear language so families can be prepared.

It is important to help families become advocates for their children. For children with behavioral conditions, this is even more important because children’s behaviors often can lead to stress and strain on peer relationships and functioning in school. However, there are terms or abbreviations that need to be explained in clear language so families can be prepared. One of the things I get asked about is whether there is a “right” way to do things when talking to parents about how to raise their children. My response? No, there is no “right” way, but there are likely other ways–especially when something a parent is doing in the moment is not working. Some times it takes another person who can be objective to think through a situation and come up with a different approach.

One of the things I get asked about is whether there is a “right” way to do things when talking to parents about how to raise their children. My response? No, there is no “right” way, but there are likely other ways–especially when something a parent is doing in the moment is not working. Some times it takes another person who can be objective to think through a situation and come up with a different approach. We have all heard the advice to praise kids more. However, that requires some clarification. We need to communicate clearly to our children what it is we like about what they are doing when they are doing it. This helps to “connect the dots” between the desired behavior and what our expectations are. As busy as we all are, we can forget that feedback is helpful, especially when you want someone to repeat a behavior again.

We have all heard the advice to praise kids more. However, that requires some clarification. We need to communicate clearly to our children what it is we like about what they are doing when they are doing it. This helps to “connect the dots” between the desired behavior and what our expectations are. As busy as we all are, we can forget that feedback is helpful, especially when you want someone to repeat a behavior again. I have been working closely with my ADHD patient advisory board (PAB) for the past several years to improve upon ongoing work examining primary care-based interventions for ADHD. It is hard to believe we are nearing the end of a 2 year process. I have witnessed the change within parents who participated in the research as a ‘subject’, then agreed to serve as a ‘consultant’ to me and my team to help us think through important study issues and brainstorm solutions as challenges arose…and finally to ‘collaborators’ in the final stages of the current study.

I have been working closely with my ADHD patient advisory board (PAB) for the past several years to improve upon ongoing work examining primary care-based interventions for ADHD. It is hard to believe we are nearing the end of a 2 year process. I have witnessed the change within parents who participated in the research as a ‘subject’, then agreed to serve as a ‘consultant’ to me and my team to help us think through important study issues and brainstorm solutions as challenges arose…and finally to ‘collaborators’ in the final stages of the current study. The idea of group visits is not new. This model has been used successfully by psychologists and therapists for a variety of issues for group therapy and patient education. The first paper using the group model in pediatrics was published in 1977 by my mentor, Dr. Martin Stein, who used groups for mother-infant care. Another set of papers were published by Dr. Lucy Osborn in the 1980s examining its use for well child care and patient education.

The idea of group visits is not new. This model has been used successfully by psychologists and therapists for a variety of issues for group therapy and patient education. The first paper using the group model in pediatrics was published in 1977 by my mentor, Dr. Martin Stein, who used groups for mother-infant care. Another set of papers were published by Dr. Lucy Osborn in the 1980s examining its use for well child care and patient education.