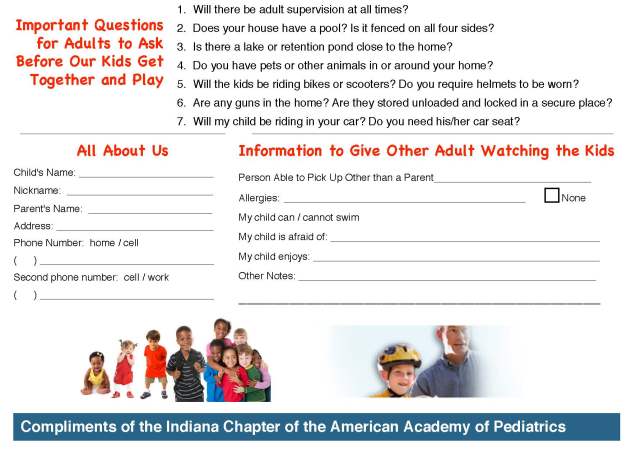

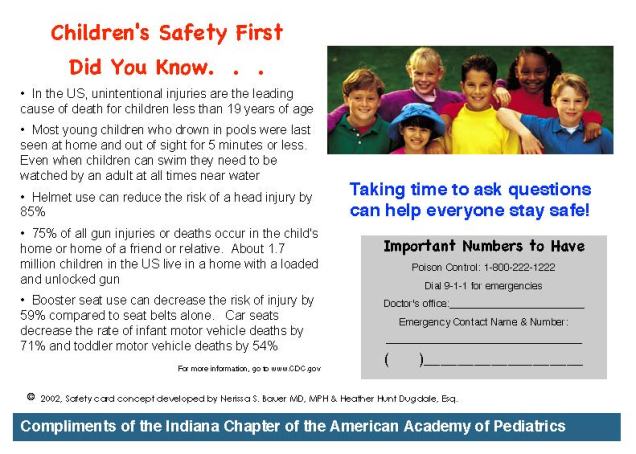

After talking with a few parents & colleagues about my last post: “Kids and Guns: It’s about Child Safety” it became clear that a follow up post was needed. While playdate cards help parents talk to other parents, what resources are there to help non-gun owning families talk to children about guns?

S0, how do you start the conversation with your child if you live in a gun-free home? When should you bring it up? Will talking make a child curious? Yes.

Children are curious about EVERYTHING.

RELATED: How I Talk to My Children About Guns

As parents, we talk to children about looking both ways before they cross the street. We talk to them about buckling up whenever in the car. We talk to them about not talking to strangers.

Talking to children about what to do if they ever find a gun or weapon in a friend’s home is just as important. Guns in US homes are common. Reasons vary for keeping guns & weapons: work, recreation or personal protection.

It is important to help your child be prepared to know what to do.

RELATED: How to End Gun Violence in the US

LISTEN TO THIS: How guns can affect families forever–StoryCorp: Gone with a Gunshot, His Little Sister Remains, Eternally 8

This handout*summarizes some key things for parents to think about before and during talking with children about guns and other weapons. It gives some suggestions on how and when to start the conversation. It also gives parents a reminder to use a matter of fact tone.

Review this handout. Share with your partner, spouse, family, friend. Then talk to your children about guns/weapons. It can help keep yet another child safe from gun violence.

And remember, talk to other parents about guns/weapons in their homes before sending your child over to play. They will not be offended.

RELATED: Blood on our Hands

*A special thank you to Dr. Mandy Harris and Rebecca Cisneros for talking through this important topic and providing suggestions for the handout!

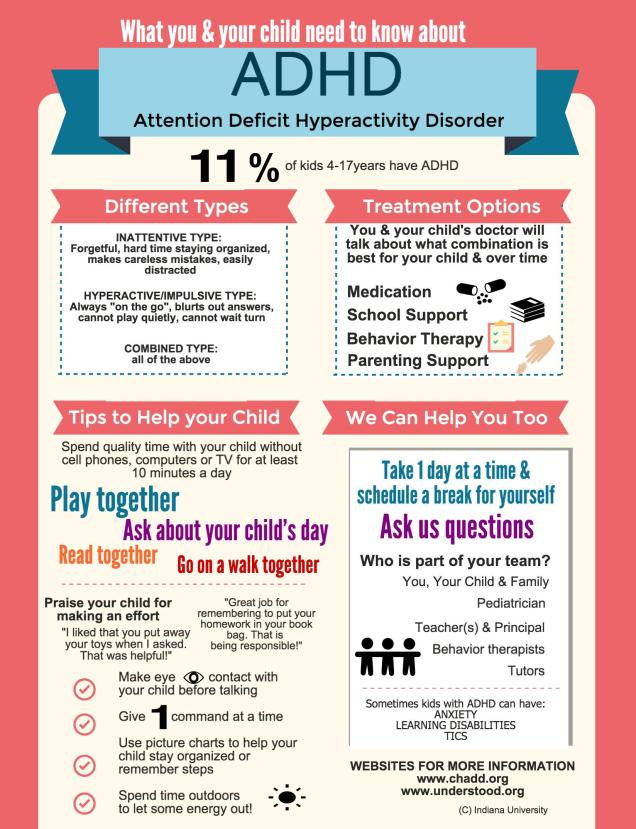

When families face chronic diseases, it is especially important to encourage their active participation with the medical team. This is the hallmark of the “chronic care model,” which encourages medical providers and the patient/family to work together. Chronic diseases often require lifestyle and behavior change to maximize outcomes. This is especially true in pediatrics and behavioral conditions. Published clinical care guidelines for all pediatric behavioral/mental health conditions (such as ADHD) highlight parent training and behavioral interventions as “first line” treatments.

When families face chronic diseases, it is especially important to encourage their active participation with the medical team. This is the hallmark of the “chronic care model,” which encourages medical providers and the patient/family to work together. Chronic diseases often require lifestyle and behavior change to maximize outcomes. This is especially true in pediatrics and behavioral conditions. Published clinical care guidelines for all pediatric behavioral/mental health conditions (such as ADHD) highlight parent training and behavioral interventions as “first line” treatments. It is important to help families become advocates for their children. For children with behavioral conditions, this is even more important because children’s behaviors often can lead to stress and strain on peer relationships and functioning in school. However, there are terms or abbreviations that need to be explained in clear language so families can be prepared.

It is important to help families become advocates for their children. For children with behavioral conditions, this is even more important because children’s behaviors often can lead to stress and strain on peer relationships and functioning in school. However, there are terms or abbreviations that need to be explained in clear language so families can be prepared. We have all heard the advice to praise kids more. However, that requires some clarification. We need to communicate clearly to our children what it is we like about what they are doing when they are doing it. This helps to “connect the dots” between the desired behavior and what our expectations are. As busy as we all are, we can forget that feedback is helpful, especially when you want someone to repeat a behavior again.

We have all heard the advice to praise kids more. However, that requires some clarification. We need to communicate clearly to our children what it is we like about what they are doing when they are doing it. This helps to “connect the dots” between the desired behavior and what our expectations are. As busy as we all are, we can forget that feedback is helpful, especially when you want someone to repeat a behavior again.