Today’s column by Valerie Strauss “If you can pay attention, you do not have ADHD”–and 9 other misconceptions about the disorder” was a great read. Ms. Strauss highlights the Top 10 Myths of ADHD by Dr. Ned Hallowell, a child and adult psychiatrist. This list is a good for families of newly diagnosed children or in situations where parents are concerned about the possibility of ADHD and have yet to get confirmation.

I have been in the position of talking to parents, to grandparents, to schools about what ADHD is and what it is not. There are a lot of myths and misconceptions about the diagnosis and treatment options.

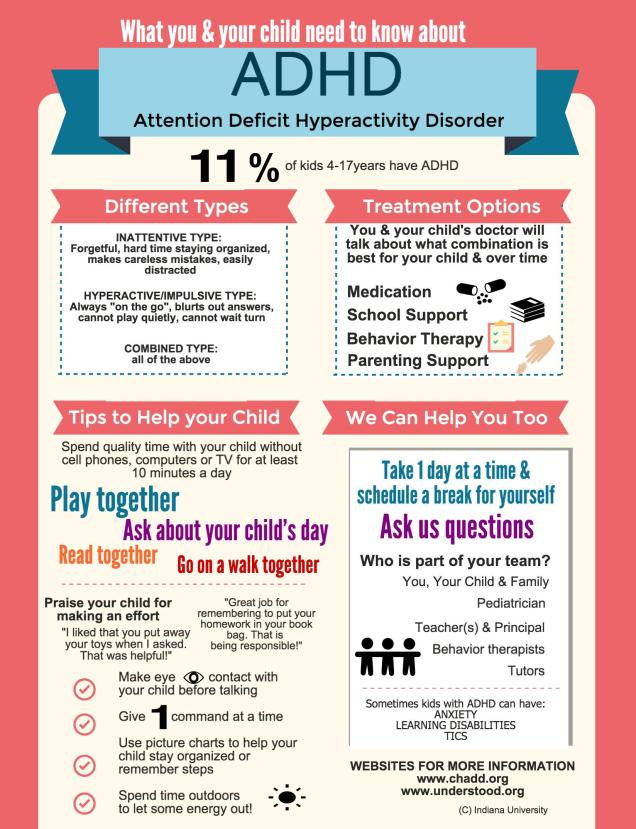

Let’s get that out of the way now. “Treatment” does not necessarily imply medication. However, I know many parents cannot stop thoughts of: “if this is ADHD, then it must mean they will want to medicate my child…” First, as a behavioral pediatrician, I want to say that having the diagnosis of ADHD does not automatically mean your child will need to be on medication. In fact, the first line “treatment” for ADHD is parent training and education.

RELATED: Treatment & Target Outcomes for Children with ADHD (from healthychildren.org)

Yes, sometimes medications are used in the treatment but educational supports, behavioral therapy and parent training or also part of the plan. These components can be started at any time, may be combined with other treatments. Sometimes treatments are dropped and added on again at later times.

These decisions are made with the family and the team (for example: doctors, teachers, therapists)–and always with the goal of asking, “What else is needed to ensure that the child is learning and doing what he/she needs to be doing every day and doing it as well as can be?”

If you are a parent with a child with ADHD or a parent who is worried that your child may have ADHD, make sure you come prepared to ask questions at each and every appointment. It can be challenging and hard to remember who is doing what since much of the time behavioral conditions require many team players. Your child’s doctor wants you to feel comfortable with every decision that has to be made along the way. They are happy to have you ask questions, no matter how many times or different iterations.

Another thing to remember is that at the time when the diagnosis is uncertain or is new, it can feel like you are all alone and overwhelming. The first step is to take a breath and write down any and all questions. Organize all paperwork and relevant schoolwork in a binder/folder and keep them together. It helps keep things handy when you have to meet yet another new team player. It also ensures that everyone is on the same page. There is nothing more stressful than not knowing which team member to call when things go awry or after a particularly challenging day. See my post “A new handout for ADHD” that I developed and use with families that can help explain some concepts I think is important to think about when a child is newly diagnosed.

The key is to remember to reach out to your child’s doctor if you have ongoing questions. Yes, they can prescribe medications for ADHD, but they can and always will be there to coordinate care and make referrals. They are interested in talking through all treatment options and linking you to great community resources and organizations. This is what the “medical home” is all about.

RELATED: Your child’s medical home: What you need to know

When families face chronic diseases, it is especially important to encourage their active participation with the medical team. This is the hallmark of the “chronic care model,” which encourages medical providers and the patient/family to work together. Chronic diseases often require lifestyle and behavior change to maximize outcomes. This is especially true in pediatrics and behavioral conditions. Published clinical care guidelines for all pediatric behavioral/mental health conditions (such as ADHD) highlight parent training and behavioral interventions as “first line” treatments.

When families face chronic diseases, it is especially important to encourage their active participation with the medical team. This is the hallmark of the “chronic care model,” which encourages medical providers and the patient/family to work together. Chronic diseases often require lifestyle and behavior change to maximize outcomes. This is especially true in pediatrics and behavioral conditions. Published clinical care guidelines for all pediatric behavioral/mental health conditions (such as ADHD) highlight parent training and behavioral interventions as “first line” treatments. It is important to help families become advocates for their children. For children with behavioral conditions, this is even more important because children’s behaviors often can lead to stress and strain on peer relationships and functioning in school. However, there are terms or abbreviations that need to be explained in clear language so families can be prepared.

It is important to help families become advocates for their children. For children with behavioral conditions, this is even more important because children’s behaviors often can lead to stress and strain on peer relationships and functioning in school. However, there are terms or abbreviations that need to be explained in clear language so families can be prepared. I have been working closely with my ADHD patient advisory board (PAB) for the past several years to improve upon ongoing work examining primary care-based interventions for ADHD. It is hard to believe we are nearing the end of a 2 year process. I have witnessed the change within parents who participated in the research as a ‘subject’, then agreed to serve as a ‘consultant’ to me and my team to help us think through important study issues and brainstorm solutions as challenges arose…and finally to ‘collaborators’ in the final stages of the current study.

I have been working closely with my ADHD patient advisory board (PAB) for the past several years to improve upon ongoing work examining primary care-based interventions for ADHD. It is hard to believe we are nearing the end of a 2 year process. I have witnessed the change within parents who participated in the research as a ‘subject’, then agreed to serve as a ‘consultant’ to me and my team to help us think through important study issues and brainstorm solutions as challenges arose…and finally to ‘collaborators’ in the final stages of the current study. The idea of group visits is not new. This model has been used successfully by psychologists and therapists for a variety of issues for group therapy and patient education. The first paper using the group model in pediatrics was published in 1977 by my mentor, Dr. Martin Stein, who used groups for mother-infant care. Another set of papers were published by Dr. Lucy Osborn in the 1980s examining its use for well child care and patient education.

The idea of group visits is not new. This model has been used successfully by psychologists and therapists for a variety of issues for group therapy and patient education. The first paper using the group model in pediatrics was published in 1977 by my mentor, Dr. Martin Stein, who used groups for mother-infant care. Another set of papers were published by Dr. Lucy Osborn in the 1980s examining its use for well child care and patient education.