It is important to help families become advocates for their children. For children with behavioral conditions, this is even more important because children’s behaviors often can lead to stress and strain on peer relationships and functioning in school. However, there are terms or abbreviations that need to be explained in clear language so families can be prepared.

It is important to help families become advocates for their children. For children with behavioral conditions, this is even more important because children’s behaviors often can lead to stress and strain on peer relationships and functioning in school. However, there are terms or abbreviations that need to be explained in clear language so families can be prepared.

Parents often rely upon their child’s pediatrician when faced with stress around their child’s behavior. However, I have learned that many pediatricians often do not feel comfortable with coaching families about educational advocacy because it is not something that is taught during training. Aside from opportunities to learn what this is all about with individual families, this is by and large a skill that is missing and thus leaves many pediatric providers uncomfortable with these questions.

Helping families become comfortable engaging with the school and being involved in their child’s education increases the likelihood of the child’s educational success at any age. Some of the positive outcomes, regardless of the family background, include:

- Higher grades and test scores

- High quality work habits and task attendance

- Regular school attendance

- Better social skills and behavior

- Graduate and go on to post-secondary education

The first step is to ensure parents are viewed and feel like an equal partner at the table when working with schools. However, if parents have not had positive experiences with the school system either as a child or with their child, it makes it less likely that the parent will know where to start.

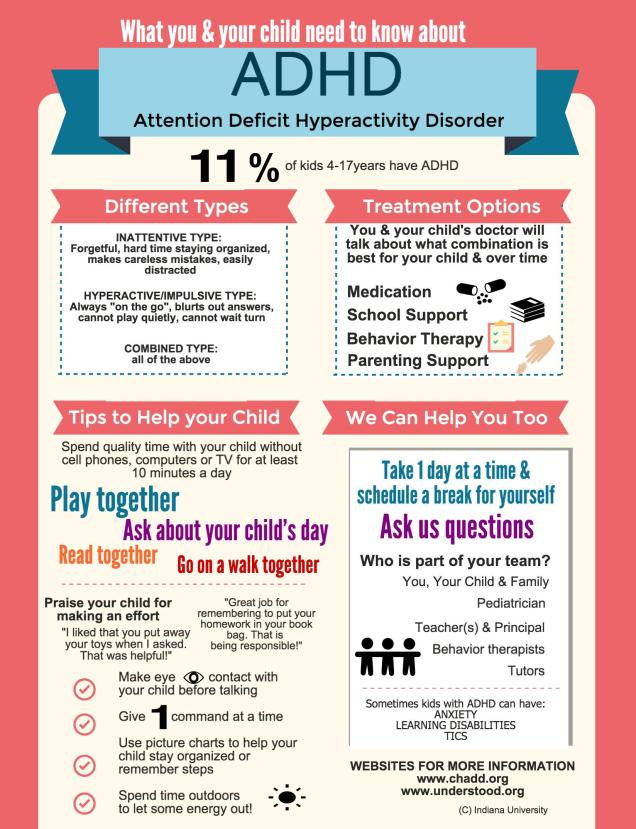

That is where pediatric providers come in and can help coach families on the importance of educational advocacy. As part of our ongoing work with ADHD group visits, one session is dedicated just to this topic because we have structured sessions to focus on the various treatment modalities for ADHD (Note: we work hard to make sure families understand that even though medications are often the first thing they think about when ADHD comes up, it is just one part of treatment. Positive parenting and educational support are equally as important!)

It also became clear that pediatric providers really crave tools to help explain the “alphabet soup” tied to understanding educational advocacy. So we engaged our patient advisory board and patient engagement core to help us translate these complex topics into something that can be used by the pediatric provider when talking with parents about interfacing with school.

We learned that parents want to hear about others’ stories about school experiences, even if it does not entirely relate to their own child. Stories are powerful ways to understand concepts or scenarios and that ‘first-hand’ experience is valuable to other parents. Moreover seeing different approaches can help families adapt to their own situation. As a result of this process, our design team came up with a “choose your own adventure.” Every aspect of this colorful brochure has been carefully thought out–right to the “pauses” rather than hard stops at each part of the story.

During our studies using this in our ADHD group visits, these tools were welcomed by parents and providers since it helped simplify the conversation and served as a nice road map for helping both parties to talk about the process.

Download a copy of the English version here.*

Download a copy of the Spanish version here.*

*Special thank you to our patient advisory board and Dr. Sarah Wiehe, Dustin Lynch, Courtney Moore (IU Patient Engagement Core) & to Helen Sanematsu.

As always, please share your experiences using these tools, whether as a parent or provider.

One of the things I get asked about is whether there is a “right” way to do things when talking to parents about how to raise their children. My response? No, there is no “right” way, but there are likely other ways–especially when something a parent is doing in the moment is not working. Some times it takes another person who can be objective to think through a situation and come up with a different approach.

One of the things I get asked about is whether there is a “right” way to do things when talking to parents about how to raise their children. My response? No, there is no “right” way, but there are likely other ways–especially when something a parent is doing in the moment is not working. Some times it takes another person who can be objective to think through a situation and come up with a different approach. We have all heard the advice to praise kids more. However, that requires some clarification. We need to communicate clearly to our children what it is we like about what they are doing when they are doing it. This helps to “connect the dots” between the desired behavior and what our expectations are. As busy as we all are, we can forget that feedback is helpful, especially when you want someone to repeat a behavior again.

We have all heard the advice to praise kids more. However, that requires some clarification. We need to communicate clearly to our children what it is we like about what they are doing when they are doing it. This helps to “connect the dots” between the desired behavior and what our expectations are. As busy as we all are, we can forget that feedback is helpful, especially when you want someone to repeat a behavior again. I have been working closely with my ADHD patient advisory board (PAB) for the past several years to improve upon ongoing work examining primary care-based interventions for ADHD. It is hard to believe we are nearing the end of a 2 year process. I have witnessed the change within parents who participated in the research as a ‘subject’, then agreed to serve as a ‘consultant’ to me and my team to help us think through important study issues and brainstorm solutions as challenges arose…and finally to ‘collaborators’ in the final stages of the current study.

I have been working closely with my ADHD patient advisory board (PAB) for the past several years to improve upon ongoing work examining primary care-based interventions for ADHD. It is hard to believe we are nearing the end of a 2 year process. I have witnessed the change within parents who participated in the research as a ‘subject’, then agreed to serve as a ‘consultant’ to me and my team to help us think through important study issues and brainstorm solutions as challenges arose…and finally to ‘collaborators’ in the final stages of the current study. The idea of group visits is not new. This model has been used successfully by psychologists and therapists for a variety of issues for group therapy and patient education. The first paper using the group model in pediatrics was published in 1977 by my mentor, Dr. Martin Stein, who used groups for mother-infant care. Another set of papers were published by Dr. Lucy Osborn in the 1980s examining its use for well child care and patient education.

The idea of group visits is not new. This model has been used successfully by psychologists and therapists for a variety of issues for group therapy and patient education. The first paper using the group model in pediatrics was published in 1977 by my mentor, Dr. Martin Stein, who used groups for mother-infant care. Another set of papers were published by Dr. Lucy Osborn in the 1980s examining its use for well child care and patient education.